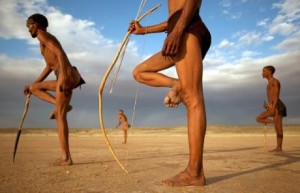

In his amazing book Future Primal, Louis Herman, a professor of political science at the University of Hawaii-West O’ahu, articulates how we should respond to our converging crisis of violent conflict, political corruption, and global ecological devastation. Herman’s sweeping synthesis is to point us back into our deepest past in order to recover our core humanity. He uncovers how important clues for our recovery can be found in the lives of traditional San Bushmen; the hunter-gatherers of South Africa and the closest living relatives to the ancestral African population from which all humans descend. This brilliant book reveals how we ought to draw from the experience of the San and other earth-based cultures and weave their wisdom together with the scientific story of an evolving universe to help create something radically new. It makes for compelling and challenging reading.

Embedded within this unfolding narrative Herman talks about the Third World Conference on Hunter Gatherers that took place in Paris in 1979. The consensus to emerge from that conference was to empathically contradict the prevailing Hobbesian assumptions on which the institutions of modernity have been founded. In brief Hobbes held that the natural condition of human beings was antagonistic and without strong government mankind was condemned to lives of violence and misery. There was need for a ‘greater authority’ if we are to co-exist peacefully. Furthermore Hobbes held that the causes for such quarrel were competition, diffidence and ‘glory’ with the dominant aims of man being gain, safety and reputation. It was this philosophical foundation that supported and justified much of modernity.

There are four illuminating insights that we can take from studies of the San and other such tribes. Four insights, that not only challenge ‘what we know’ (or think we know), but that offer a glimpse into ‘another way’, perhaps even, ‘a better way’. They are certainly not ‘new’ in that we talk and write about them all the time; it is just that somehow they have become dislocated from who we are and how we live and work. They have become concepts stripped of both meaning and application in contemporary living and we are the poorer for it.

The areas covered by the four insights are:

- Balance: Although poor in personal material wealth, these people had more leisure time than any society since. This is rather sobering is it not? We work so hard to enjoy the ‘fruits of our labour’ and we strive in order to enjoy ‘things’ together with those important to us, yet the exact opposite has emerged. The San worked for what they needed, no more, no less. Their balance was something we constantly strive for and yet the more we talk about it and work for it, the more illusive it becomes. For many, ‘life-work’ balance is a myth, a dream beyond reach. The lack of internal and external balance has dire consequences at both a personal and global level.

- Community: The world of the San was not a ‘dog-eat-dog’ world as we so often are led to believe. Rather it was a world of self-sustaining communities, resilient and in harmony with those with whom there was a shared interdependence. Utopian by today’s standards? Perhaps, but no less instructional nonetheless. Understanding our businesses and the people within as communities where we strive for a measure of self-sustainability would evoke discussion and action that might just substantially change things for the better. The machine metaphor, a legacy of the Industrial Era, which characterises our business form, thinking and language, is on life-support. The machine needs to be turned-off and we need new thinking, new expression and new descriptors to take us into the future. Seeing our business as a village, or as a community, is a good place to start such a journey.

- Caring: Theirs was a community, a society, based on mutual caring and sharing. The San understood that their very survival depended on such and it was entrenched in how they lived. The Native American ethos is similar where there was no personal ownership but rather a collective understanding that resources were to be used for the common good. Immediately you might be thinking of the grand experiments of socialism and communism, neither of which worked as political dispensations, yet are not entirely without merit when stacked against where it is that rampant, unchecked capitalism has taken us. Without getting into deeper debates around such issues, seeing our businesses as ‘communities’ makes caring and sharing unavoidable. As human beings we know this is important – after all we practice it in our family units daily; how would it look were we to extend it to those with whom we share a common purpose through the work that binds us together? An honest engagement with such matters, although seemingly impossible or utopian, would have a dramatic impact on the way we do things and I suspect, incur multiple benefits.

- Decision-making: Decisions were collective practice and there were no powerful chiefs. Again, taken in its ‘raw form’ this is hard to imagine and even harder to think about implementing. However, in the adaptive leadership model – finding solutions for new problems or ‘knowing what to do when you don’t know what to do’ necessitates all the stakeholders being involved. The adaptive nature of the challenges we encounter requires that all the stakeholders have a voice and share in the new learning that is essential if progress is to be made. This is a fundamental shift from situations where an authoritative voice held sway or there existed a ‘command and control’ type approach. All too often leadership practice is understood as and based on title, position and authority – and the ensuing results are plain for all to see.

If the world has changed we need to think and act differently. The world has changed. Corporate leaders know this but are struggling with forces within and without that refuse to move, change and adapt. There are legacy constraints that resist the needed innovation, experimentation and flexibility. Of course, change is not optional if we are to survive and ultimately thrive into the future. Leaders will have to look in new places for their inspiration as they lead through the volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity that characterises our current context. Asking the ‘right’ questions and knowing where to look, will make the difference as to whether your business lives or dies. It is that simple, it is that complex.

The San Bushmen might just be the place to start. ‘Future Primal’…Louis Herman points the way but forging the pathway, well that is our responsibility.