Today’s insights are brought to you by my colleague and global futurist, Graeme Codrington.

In this article we’re going to address cognitive bias. This is vitally important and will probably take some time to work through. There are some exercises to help you challenge your internalised biases, including some videos to watch and some recommended reading.

This topic is one of the most important cornerstones to improving your critical thinking skills. Cognitive bias is when our brain takes shortcuts in thinking, leading us away from clear, logical decisions. Our brains are the most powerful computers on the planet. In order to work well, our brains have developed many different shortcuts to making decisions. Although we manage some of these shortcuts consciously, most happen without our knowledge at a subconscious level.

This isn’t just a random mistake; it’s a built-in feature of how our minds work. There’s nothing wrong with this – in fact, if our brains didn’t do this, they wouldn’t work for us at all. We get way too many inputs and there are way too many things for us to consider when making decisions, so our brains have to summarise, select and shortcut in order to get to any sort of coherent thought or outcome. This normally serves us well.

However, while these shortcuts can save time, they can also lead us to make errors in judgment or see things inaccurately. We call these errors and mistakes cognitive biases.

Here are some examples of how this works:

Example 1:

Question: Are words in English more likely to start with a K, or have a k as their third letter?

Answer: They are twice as likely to have k as the third letter. But our minds find it easier to think of words that start with K, so we default to this as our answer.

Example 2:

Here is a multiplication quiz. You need to do this in your head and take less than 5 seconds to complete it. Unless you’re a mathematics genius, you’re going to have to guess the answer and provide just an estimate. Are you ready?

Multiply these numbers together:

9 x 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

What’s your best guess at the answer?

● Is it about 230,000?

● Or 200,000?

● or about 170,000?

● Or something else?

Answer: Would it surprise you to discover the real answer is actually 362,880.

This is an example of anchoring. Unless you’re a mathematics whizz kid, the fact that I suggested some answers for you “anchored” your most likely response. Because I anchored you lower than the real number and then reduced it even further, you probably selected a number much lower than the actual 362,880. If you were close to the real number, you might have double guessed yourself and written a number lower than your actual guess. If I had anchored you at about half a million, you’d have guessed too high.

How did you do with these simple tests? And what did you think of how your brain can be manipulated and fooled

Watch this 90 second video to see some more examples of how our brain takes in data:

In our increasingly complex, ambiguous and fast-paced world, unfortunately our brains are proving to be a little bit outdated. We’re in need of an upgrade. The easiest upgrade available is to identify, recognise and accept our cognitive biases, and then develop skills and techniques to overcome them. Our brains can be trained to do this.

What goes wrong?

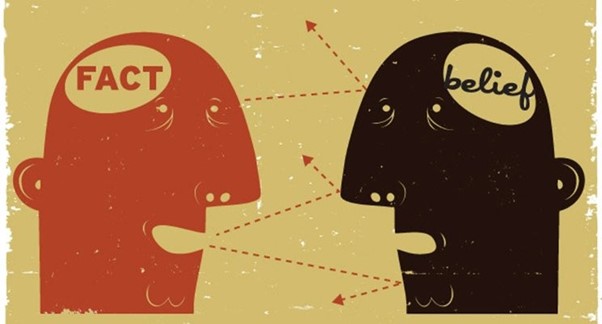

We’d like to imagine that our beliefs are rational, logical and objective. However, the fact is that our ideas are often based on incomplete information, faulty memories or incorrect analysis of the information that is available.

Cognitive bias errors can be classified as either belief perseverance (our inability to accept new information that contradicts existing beliefs) or processing errors (failure to manage and organise information properly, either through errors of judgement or lack of capacity to compute and analyse data). Note that we’re not talking about logical fallacies – these stem from an error in a logical argument.

Cognitive bias is rooted in thought-processing errors, where the logic might be correct, but the selection or weighting of data leads one person to one outcome and another to something completely different.

Cognitive biases are not necessarily all bad. In fact, they’re necessary: they allow us to reach decisions quickly, or even reach decisions at all. Since attention is a limited resource, we have to be selective about what we pay attention to, and this allows biases to creep in and influence the way we see and think about the world. If we had to think about every possible option when making a decision, it would take too much time to make even the simplest choices. Shortcuts are necessary. These mental shortcuts are technically known as heuristics.

While they can often be surprisingly accurate, they can also lead to errors in thinking – and they often do. In addition, cultural prejudices, social pressures, individual motivators, emotions and limits on our mind’s ability to process information can also contribute to these biases.

Watch this 6-minute video to alert yourself to the impact cognitive biases can have in the workplace:

Extra resources:

If you’d like more information at this point, here are two videos of about 15 minutes each which give you some more introductions to the topic. The first video has a psychology-based focus, and the second comes from the world of investing and finance. Both focus on an introduction to cognitive bias:

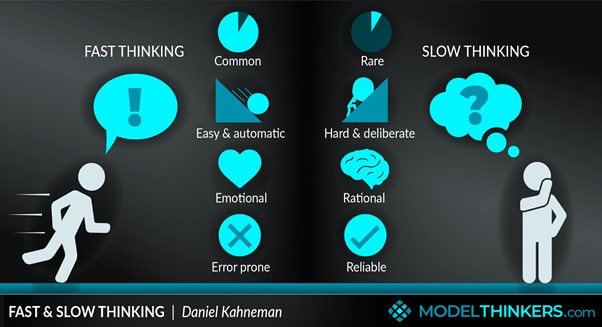

You should also add Daniel Kahneman’s excellent book, Thinking Fast and Slow to your reading list. Along with his colleague, Amos Tversky, Kahneman identified that our brains have two distinct ‘operating systems.’

System 1 is fast, gullible and jumps to conclusions. This is our ‘fast brain.’ System 2 is slow, laborious, painstaking and is “in charge of doubting and unbelieving” but “sometimes busy and often lazy.”

It’s this mix of speed in System 1 and System 2’s “laziness” that causes cognitive bias. Where our brain jumps to a quick conclusion, rather than working out the answer methodically through our slow brains.

Kahneman gives a frightening real world example: in an analysis of over 1,000 decisions made by Israeli parole board judges, it was discovered that the judges freed prisoners in up to 65% of cases straight after meals and snacks. But the rate fell close to zero just before breaks.

The last prisoner evaluated before a refreshment break was never released. How crazy is that? Being tired or hungry reduces our capacity to think, so we revert to easy options and defaults. These easy options and defaults can impact and change people’s lives, not always for the best.

Someone’s life might not depend on the next decision you make, but it’s still important to recognise, understand and deal with cognitive biases when we can.

There are literally hundreds of cognitive biases. If you’d like to access our full article on this topic, please click through here to where we deal with a few categories of the most important biases. With each one, we’ll give a definition, some examples, implications and some suggestions for dealing with it. Changing how your brain reacts and processes information takes time and intentionality.

Some of the examples our in-depth article addresses include:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs while ignoring information that challenges them.

- Anchoring: The habit of relying too heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions.

- Recency Bias: The inclination to weigh the latest information more heavily than older data.

- Availability Heuristic: The tendency to overestimate the importance of information that is easily recalled or accessed.

- Framing & Priming: The influence of context or presentation on how information is interpreted and remembered.

- Bandwagon or Conformity Bias: The tendency to adopt beliefs or actions because they are popular or accepted by a group.

- Authority Bias: The inclination to place undue value on the opinions of perceived experts or authority figures.

- Self-Serving Bias: The habit of attributing successes to one’s own abilities while blaming external factors for failures.

The cognitive biases above are common, but they represent only a small fraction of all the documented cognitive biases. Don’t become despondent or disillusioned at how easy it is for us to be fooled. But equally, don’t ignore this issue, thinking it’s too big an issue to do anything about.

Understanding these cognitive biases is more than an academic exercise; it’s a vital step toward enhancing decision-making and organisational effectiveness. Awareness alone can serve as a potent corrective measure, making you more critical of the data and opinions that cross your desk. But the true power lies in proactively counteracting these biases.

By doing so, leaders can make more informed decisions based on a comprehensive view of facts, which ultimately leads to better outcomes. A bias-free environment also boosts innovation, as ideas are evaluated on their merits rather than through the lens of preconceived notions.

Moreover, tackling biases has ethical implications, ensuring that choices are fair and just. In a complex and competitive global landscape, the ability to think clearly and rationally, and the ability to rethink and reconceptualise, will be some of the most valuable assets leaders can cultivate.

For the past two decades, Graeme has worked with some of the world’s most recognized brands, travelling to over 80 countries in total, and speaking to around 100,000 people every year. He is the author of 5 best-selling books, and on faculty at 5 top global business schools.