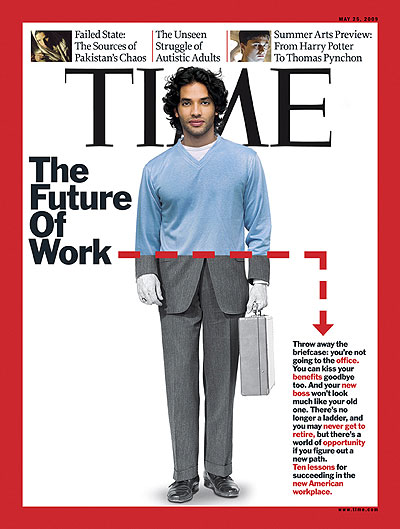

I think they do it every other year, and it makes a great cover. TIME magazine at the end of May 2009 was focused on the issue of ‘The Future of Work’. You can read it at TIME’s website, or below.

I think they do it every other year, and it makes a great cover. TIME magazine at the end of May 2009 was focused on the issue of ‘The Future of Work’. You can read it at TIME’s website, or below.

The article takes the form of ten short insights. The highlights for me are:

- Companies are going to have to become very innovative to create new types of perks, incentives and motivators for staff

- Boomers now definitely can’t – and won’t retire – as planned. We’ve been talking about this for some time, but now the reality is here. See our Prime Time presentation if you want more info.

- Gen Xers are coming into senior leadership – and it’s going to be different.

- It pays to save the planet. Again, we’ve been saying this for a while. But now it’s becoming a strategic imperative – see The Future is Now.

- We really do need to start working from home now. Enough talking about it!

TIME Magazine

25 May 2009

The Way We’ll Work

Ten years ago, Facebook didn’t exist. Ten years before that, we didn’t have the Web. So who knows what jobs will be born a decade from now? Though unemployment is at a 25?year high, work will eventually return. But it won’t look the same. No one is going to pay you just to show up. We will see a more flexible, more freelance, more collaborative and far less secure work world. It will be run by a generation with new values — and women will increasingly be at the controls. Here are 10 ways your job will change. In fact, it already has.

High Tech, High Touch, High Growth

By ALEX ALTMAN

On a gloomy afternoon earlier this month, a group of Harvard students took a break from crafting final papers to peer into the future. Surveying a shattered employment landscape, they summoned the optimism to regard looming obstacles as opportunities for scenic detours. “There are definitely downsides to it being harder to get a job,” says Alex Lavoie, a 21-year-old junior from Avon, Conn. “But it’s forced people to look harder at what they really want to do instead of following a standardized path.”

During the fat years, that path led many of America’s élites to Wall Street. These days, that’s a less appealing destination. In 2008 the financial sector, which had ballooned over the past three decades, contracted for the first time in 16 years. “The glamour is gone,” says Bridget Beckeman, 20, a junior from Westford, Mass., who will intern at an investment bank this summer. But it hasn’t disappeared. Financial centers like Charlotte, N.C., will flourish anew; driven largely by a banking boom, the city’s workforce has grown 50% over the past decade, according to John Connaughton, a professor of economics at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

The fall of finance has its upside. Top grads will tack toward a variety of potentially lucrative positions that prize technological savvy and analytical aptitude. According to consulting giant McKinsey & Co., nearly 85% of new jobs created between 1998 and 2006 involved complex “knowledge work” like problem-solving and concocting corporate strategy. Job opportunities in mathematics and across the sciences are also expected to expand. The U.S. Department of Labor spotlights network systems and data communications as well as computer-software engineering among the occupations projected to grow most explosively by 2016. Over the next seven years, the number of jobs in the information-technology sector is expected to swell 24% — a figure more than twice the overall job-growth rate.

There will be some limits to that growth. “This place is going to get more and more high-end talent and less and less commodity-type folks,” says Mark Dinan, a Silicon Valley recruiter. “The real question is, What’s the next big thing, and what’s going to be the big moneymaker?” Cloud computing? Nanotechnology? Genomics? The answer will come from the companies that entrepreneurs can create — and destroy — more easily than ever before, because the cost of start-ups is dropping rapidly. Richard Freeman, director of the labor studies program at the National Bureau of Economic Research, says that “these really sharp, aggressive, Harvard-type students doing entrepreneurship, forming new businesses … would be the best thing that could happen to this economy.”

Where else could your next job come from? Health care and education, the labor market’s traditional bulwarks in lean times, show no signs of abating. An aging population will open up opportunities too. “Construction of senior communities, assisted-living facilities, nursing homes … these things are all going to have to expand tremendously,” says Connaughton. The key to finding the jobs of the future will be knowing where to look.

— With reporting by Steve Goldberg / Charlotte and Matt Villano / San Francisco

Training Managers to Behave

By JUSTIN FOX

It’s commencement day at the Thunderbird School of Global Management, a highly regarded if off-the-beaten-track business school housed on a former military base (Thunderbird Field) in Glendale, Ariz., a suburb of Phoenix. The 279 graduates have gathered on a May afternoon in a convention center next door to the Arizona Cardinals football stadium. After a presentation of the flags of 35 nations and a speech by school president Angel Cabrera, something unusual happens.

“As a Thunderbird and a global citizen, I promise,” Cabrera begins. The graduates repeat after him. Then the recitation continues:

I will strive to act with honesty and integrity. I will respect the rights and dignity of all people. I will strive to create sustainable prosperity worldwide. I will oppose all forms of corruption and exploitation. And I will take responsibility for my actions. As I hold true to these principles, it is my hope that I may enjoy an honorable reputation and peace of conscience.

This is the Thunderbird Oath of Honor, the unlikely leading edge of an assault on business as usual at business schools. It’s part of a broader rethinking of the balance between doing well and doing good that could reshape the economy and the workplace in coming years — or could just stay a debating point. B schools, Thunderbird president Cabrera and his fellow rebels contend, are ethical wastelands partly to blame for the Wall Street collapse of the past year. Even those who defend B schools don’t claim that they’re moral beacons. Debating Cabrera in April at the annual convention of the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), Purdue business-school dean Richard Cosier attributed the crisis to “personal greed” and too much debt. “Personal greed reflects personal values,” Cosier asserted when I caught him on the phone a few days later, “and you can’t blame business schools for determining personal value systems.”

There was a time, in the first half of the 20th century, when business schools did try to instill values and norms. They aimed to establish a profession of management that took its cues from medicine and the law. That effort fizzled by the 1970s, says Rakesh Khurana, a Harvard Business School prof whose 2007 history, From Higher Aims to Hired Hands, chronicles the shift. Khurana, a close ally of Cabrera’s, argues that business schools have become trade schools focused on securing the highest-paying jobs for their graduates. “If you wonder why CEOs spend so much time thinking about whether their bathrooms are up to par,” Khurana says, “look at the business schools they went to.”

Khurana was a keynote speaker at the April AACSB convention, and he doesn’t think his message went over well. “Two hours of making 1,200 people squirm in their seats” is how he describes it. It’s not just business educators who squirm at the idea of management as a profession. When I mentioned it to a lawyer friend, he scoffed, “It doesn’t work unless you have a professional exam, a licensing board and exposure to malpractice.” Cabrera and Khurana agree. “The biggest question is — and we don’t know the answer — How are we going to institutionalize this?” Cabrera says. We’re a long way from a world where you could lose your management license for taking shortcuts to meet a quarterly-earnings target. But we do have the Thunderbird Oath.

Cabrera, a Spaniard with a psychology Ph.D. from Georgia Tech, introduced a similar oath as dean of a business school in Madrid, but it was abandoned after he left in 2004. In hopes of making the concept stick at Thunderbird, he put students in charge of writing the oath and getting faculty and trustee approval. Applicants to Thunderbird must write an essay discussing the oath, and students say it often comes up in class. A few don’t love it. One student circulated an essay this spring declaring his unwillingness to sign or recite the “insulting,” “tacky” oath. Not that it kept him from graduating: even at Thunderbird, making ethical promises mandatory is still seen as beyond the business-school pale.

The Search for the Next Perk

By JOHN CURRAN

Was it a mirage? Not just our formerly fat 401(k)s but also the whole idea of a comfortable work life followed by an evergreen retirement, replete with health coverage, perks aplenty and — oh, yes — pension checks as far as the eye could see.

Faced with the rapidly rising costs of such benefits, companies are scaling back. It’s become distressingly clear that employees are increasingly on their own when it comes to retirement savings and health care.

Employers don’t typically trash an important employee benefit — too much negative press — but they are shifting more of these costs onto workers, who feel it in the form of higher health-care premiums, rising co-payments on drugs and much less certainty about their retirement finances. You may be able to preserve your benefits in your next job. But you’ll have to spend more of your own money to do so.

Towers Perrin, a global human-resources-consulting firm, recently surveyed hundreds of U.S. companies representing more than 13 million employees on changes they are making — or contemplating making — to their employee-benefits packages. The knife cuts deepest on the most expensive benefits, with the biggest often being health care.

It costs the average American company more than $14,000 per year to provide coverage to an employee and her family. The employer response: shift more of that growing burden to workers. As a result, companies have seen their health-care spending rise 29% over the past five years, but employees have seen their outlays — for premiums, co-pays and deductibles — rise 40%.

Retiree health care is getting whacked hardest — just when the boomer generation needs it most. Of the employers surveyed, 45% have already reduced or eliminated subsidized health-care coverage for future retirees, and an additional 24% are planning to do so or considering it. Of those offering the perk, roughly 25% put a dollar cap on how much they will spend per retiree. “Once the cap is reached, future inflation risk transfers to the retiree,” notes Ron Fontanetta, an executive with Towers Perrin.

Corporate pensions, the third leg of the proverbial retirement stool (the other two being Social Security and personal savings), are also being eroded as the foundering stock market wreaks havoc on employer pension funds. At the end of 2008, employer-sponsored pension plans were underfunded by more than $400 billion, according to Mercer, a management-consulting firm. The recent stock-market rally has halved that deficit, but it remains a funding sore spot and is one more reason that companies are turning away from this benefit. In mid-May, Cigna, the big insurer, joined a growing list of employers in announcing that it was “freezing” its pension plan — ending the accrual of new pension benefits for its workforce.

“Companies initiated many of these benefits in a different time,” says Fontanetta. “Retiree benefits started being offered when many companies had a young workforce with few retirees, so it was not really a cost they had to contend with.” Today it’s the reverse, particularly in old-line industries. Detroit’s Big Three automakers, for example, have more than four times as many retirees as active hourly workers.

Yet as some benefits disappear, others are blossoming, better suited to business realities and, in some ways, more prized by the younger workers that companies want to attract. That can mean account-based plans, like the 401(k), with a generous employer match (in flush times), or a more recent innovation known as the cash-balance pension. It treats younger workers better than traditional pensions because it’s based on pay and ignores tenure. It stacks up well against 401(k)s too because it typically grows with a fixed rate of return, so it will not be upended by a bear market.

And what will become of employer-sponsored health care? A little over a year ago, Towers Perrin asked workers to rank specific benefits and perks. The 45-and-over age groups ranked base pay and health care as their top two. The 18-to-34 age groups — the workers employers have their eye on — ranked base pay along with career advancement as their top priorities. The younger workers did not rank “retirement benefits” in their top 10, while that choice ranked third for the over-55s.

Too bad, boomers. You are no longer calling the tune on benefits.

We’re Getting Off the Ladder

By LAURA FITZPATRICK

On the worst days, Chris Keehn used to go 24 hours without seeing his daughter with her eyes open. A soft-spoken tax accountant in Deloitte’s downtown Chicago office, he hated saying no when she asked for a ride to preschool. By November, he’d had enough. “I realized that I can have control of this,” he says with a small shrug. Keehn, 33, met with two of the firm’s partners and his senior manager, telling them he needed a change. They went for it. In January, Keehn started telecommuting four days a week, and when Kathryn, 4, starts T-ball this summer, he will be sitting along the baseline.

In this economy, Keehn’s move might sound like hopping onto the mommy track — or off the career track. But he’s actually making a shrewd move. More and more, companies are searching for creative ways to save — by experimenting with reduced hours or unpaid furloughs or asking employees to move laterally. The up-or-out model, in which employees have to keep getting promoted quickly or get lost, may be growing outmoded. The changing expectations could persist after the economy reheats. Companies are increasingly supporting more natural growth, letting employees wend their way upward like climbing vines. It’s a shift, in other words, from a corporate ladder to the career-path metaphor long preferred by Deloitte vice chair Cathy Benko: a lattice. (See pictures of cubicle designs submitted to The Office.)

At Deloitte, each employee’s lattice is nailed together during twice-a-year evaluations focused not just on career targets but also on larger life goals. An employee can request to do more or less travel or client service, say, or to move laterally into a new role — changes that may or may not come with a pay cut. Deloitte’s data from 2008 suggest that about 10% of employees choose to “dial up” or “dial down” at any given time. Deloitte’s Mass Career Customization (MCC) program began as a way to keep talented women in the workforce, but it has quickly become clear that women are not the only ones seeking flexibility. Responding to millennials demanding better work-life balance, young parents needing time to share child-care duties and boomers looking to ease gradually toward retirement, Deloitte is scheduled to roll out MCC to all 42,000 U.S. employees by May 2010. Deloitte executives are in talks with more than 80 companies working on similar programs.

Not everyone is on board. A 33-year-old Deloitte senior manager in a southeastern office, who works half-days on Mondays and Fridays for health reasons and requested anonymity because she was not authorized to speak on the record, says one “old school” manager insisted on scheduling meetings when she wouldn’t be in the office. “He was like, ‘Yeah, I know we have the program,'” she recalls, “‘but I don’t really care.'”

Deloitte CEO Barry Salzberg admits he’s still struggling to convert “nonbelievers,” but says they are the exceptions. The recession provides an incentive for companies to design more lattice-oriented careers. Studies show telecommuting, for instance, can help businesses cut real estate costs 20% and payroll 10%. What’s more, creating a flexible workforce to meet staffing needs in a changing economy ensures that a company will still have legs when the market recovers. Redeploying some workers from one division to another — or reducing their salaries — is a whole lot less expensive than laying everyone off and starting from scratch.

Young employees who dial down now and later become managers may reinforce the idea that moving sideways on the lattice doesn’t mean getting sidelined. “When I saw other people doing it,” says Keehn, “I thought I could try.” As the compelling financial incentives for flexibility grow clearer, more firms will be forced to give employees that chance. Turns out all Keehn had to do was ask.

Why Boomers Can’t Quit

By STEPHEN GANDEL

Even before the financial crisis, many baby boomers hadn’t saved enough for retirement. Then stocks plummeted. In 1998, the average 50-year-old who had been working for at least 10 years had a 401(k) balance of $85,000, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute. Factor in the recent market drop, and more than a decade later, that worker’s 401(k) has grown to just $93,000. In short, we keep getting older, but our 401(k) balances, they stay the same.

Investment firm T. Rowe Price calculates that the oldest boomers will have to delay retirement by nearly nine years in order to recover what they lost in the market. The somewhat good news is that if they defer Social Security and save 25% of their salary, they can reach their golden years in half the time. And it’s not just boomers. With the expectation that stocks and real estate will yield less in the future, all of us will have to push back our retirement. Bottom line: “We will have to work longer and harder than we had planned,” says Steven Davis, visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

In the next year or so, older workers hanging on will make things worse. Retirement waves usually smooth recessions, as 60-somethings quit, start spending pensions and savings, and make room for younger workers. This time, though, economists think the unemployment rate will surpass 10% for the first time in decades — in part because the normal retirement cycle has been disrupted.

But once the downturn is done, the presence of older workers could be a positive. When more people work, more people spend freely, and that creates jobs. For example, women entering the workforce in the 1960s and ’70s didn’t cause permanently higher unemployment. There were positive offsets instead: demand for child-care workers took off, the prepared-foods industry boomed. And unemployment rates in the following decades hit new lows. What’s more, as jobs in traditional corporate America filled up, more people struck out on their own. New companies were formed. New industries popped up.

A healthy supply of older workers can be the salve for one of the worst types of economic poison — inflation. That may make it harder to get a raise, but it will also lead to higher profits, lower-priced goods and a stronger economy.

Boomers will try to hang on to their jobs en masse. This isn’t just any generation — it’s the largest, making up 38% of the workforce. Some believe that the U.S. economy is too mature to rapidly create great numbers of new jobs — or at least the traditional kind. Already, older workers are crowding out the younger generation. According to the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University, employment rates for teens and 20-somethings this decade have fallen, while the number of Americans 55 and older who have jobs has gone up.

That’s not all bad either. Young workers are much more flexible when it comes to finding work. They will be more likely to start businesses, embrace new technologies and industries, come up with new ideas to make money and take lower wages. “In downturns, there’s more grumbling when the Old Guard is not exiting at the usual rate,” says Claudia Goldin, an economics professor at Harvard University. “But the economy has great absorptive capacity. As long as no one is being forced, more people participating in the workforce is better for everyone.”

So, over the next decade, have some respect for those working graybeards. By choosing not to retire, they may be doing you a favor.

Women Will Rule Business

By CLAIRE SHIPMAN AND KATTY KAY

Work-life balance. In most corporate circles, it’s the sort of phrase that gives hard-charging managers the hives, bringing to mind yoga-infused, candlelit meditation sessions and — more frustratingly — rows of empty office cubicles.

So, what if we renamed work-life balance? Let’s call it something more masculine and appealing, something like … um … Make More Money. That might lift heads off desks. A few people might show up at a meeting to discuss that new phenomenon driving the bottom line: Women, and the way we want to work, are extremely good for business.

Let’s start with the female management style. It turns out it’s not soft; it’s lucrative. The workplace-research group Catalyst studied 353 Fortune 500 companies and found that those with the most women in senior management had a higher return on equities — by more than a third.

Are the women themselves making the difference? Or are these smart firms that make smart moves, like promoting women? There is growing evidence that in today’s marketplace the female management style is not only distinctly different but also essential. Studies from Cambridge University and the University of Pittsburgh suggest that women manage more cautiously than men do. They focus on the long term. Men thrive on risk, especially when surrounded by other men. Wouldn’t the economic crisis have unfolded a bit differently if Lehman Brothers had had a few more women on board?

Women are also less competitive, in a good way. They’re consensus builders, conciliators and collaborators, and they employ what is called a transformational leadership style — heavily engaged, motivational, extremely well suited for the emerging, less hierarchical workplace. Indeed, when the Chartered Management Institute in the U.K. looked ahead to 2018, it saw a work world that will be more fluid and more virtual, where the demand for female management skills will be stronger than ever. Women, CMI predicts, will move rapidly up the chain of command, and their emotional-intelligence skills may become ever more essential.

That trend will accelerate with the looming talent shortage. The Employment Policy Foundation estimated that within the next decade there would be a 6 million – person gap between the number of college graduates and the number of college-educated workers needed to cover job growth. And who receives the majority of college and advanced degrees? Women. They also control 83% of all consumer purchases, including consumer electronics, health care and cars. Forward-looking companies understand they need women to figure out how to market to women.

All that — the female management style, education levels, purchasing clout — is already being used, by pioneering women and insightful companies, to create a female-friendly working environment, in which the focus is on results, not on time spent in the office chair. On efficiency, not schmoozing. On getting the job done, however that happens best — in a three-day week, at night after the kids go to bed, from Starbucks.

And here’s the real kicker. When a company gives employees freedom, it doesn’t just feel good or get shiny, happy workers — productivity goes up. Ask firms like Capitol One, which runs a company without walls or mandatory office time. Or Best Buy, which implemented a system called ROWE — results-only work environment — and found that productivity, in some cases, shot up 40%. Flexibility is no longer a favor to be handed out like candy at a children’s birthday party; it’s a compelling business strategy.

So we need to get rid of the nutty-crunchy moral component of the work-life balance and make a business case for it. It’s easy to do. In fact, a decade from now, companies will understand that hiring lots of women, and letting them work the way they want, will help them Make More Money.

It Will Pay to Save the Planet

By BRYAN WALSH

It’s no secret that U.S. workers are in trouble, with the unemployment rate at 8.9% and rising. At the same time, the world faces a long-term climate crisis. But what if there is a way to solve both problems with one policy? A number of environmentalists and economists believe that by implementing a comprehensive energy program, we can not only avert the worst consequences of climate change but also create millions of new jobs — green jobs — in the U.S. “We can allow climate change to wreak unnatural havoc, or we can create jobs preventing its worst effects,” President Barack Obama said recently. “We know the right choice.”

What’s a green job? It depends on whom you ask. Some categories are obvious: if you’re churning out solar panels, you’re getting a green paycheck. But by some counts, so are steelworkers whose product goes into wind turbines or contractors who weatherize homes. According to a report by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, there are already more than 750,000 green jobs in the U.S.

Environmental advocates say that with the right policies, those job figures could swell. The Mayors’ report predicts that for the next three decades, green employment could provide up to 10% of all job growth. As part of its stimulus package, the White House directed more than $60 billion to clean-energy projects, including $600 million for green-job-training programs. The hope is that capping carbon emissions, even if it raises energy prices in the short term, will create a demand for green jobs, which could provide meaningful work for America’s blue collar unemployed.

To some critics, that sounds too good to be true. In a recent report, University of Illinois law professor Andrew Morriss argued that estimates of the potential for green employment vary wildly and that government subsidies would be less efficient — and produce lower job growth — than the free market. “This is all smoke and mirrors,” says Morriss. “I don’t see how you can replace the existing jobs that may be lost.”

The reality is somewhere between the skeptics and the starry-eyed greens. We won’t be able to create a solar job for every unemployed autoworker. But with climate change a real threat, shifting jobs from industries that harm the earth to ones that sustain it will become an economic imperative.

When Gen X Runs the Show

By ANNE FISHER

By 2019, Generation X — that relatively small cohort born from 1965 to 1978 — will have spent nearly two decades bumping up against a gray ceiling of boomers in senior decision-making jobs. But that will end. Janet Reid, managing partner at Global Lead, a consulting firm that advises companies like PepsiCo and Procter & Gamble, says, “In 2019, Gen X will finally be in charge. And they will make some big changes.”

They’ll have to, because the workforce Gen Xers will be leading will have altered almost beyond recognition. For one thing, Generation Y — the tattooed, techno-raised bunch born from 1979 to 2000 — is unlikely to follow in their parents’ footsteps. They think putting in long years of effort at any one company in exchange for a series of raises and promotions is pointless — not that they’ll get the chance. “Paying your dues, moving up slowly and getting the corner office — that’s going away. In 10 years, it will be gone,” says Bruce Tulgan, head of the consulting firm Rainmaker Thinking, based in New Haven, Conn., and author of a new book about managing Gen Y called Not Everyone Gets a Trophy. “Instead, success will be defined not by rank or seniority but by getting what matters to you personally,” whether that’s the chance to lead a new-product launch or being able to take winters off for snowboarding. Tulgan adds, “Companies already want more short-term independent contractors and consultants and fewer traditional employees because contractors are cheaper. And seniority matters less and less as time goes on, because it’s about the past, not the future.”

Superannuated boomers won’t vanish from the workplace altogether: people in their 60s and 70s — because of either need or desire — will be among the 40% of the U.S. workforce that will rent out its skills. “Boomers will be working part-time as coaches, strategists and consultants,” predicts Joanne Sujansky, a co-author of a book due out in June called Keeping the Millennials. “By 2019, there will be many more of those opportunities than there are now because boomers will need the income and companies will need their expertise.” Says Reid: “We’ll see an increase in job-sharing at very senior levels. You might have two boomers who share the job of chief financial officer, for instance, which lets them keep working and also have some leisure time.”

The Gen X managers who will be holding all this together will need to be adept at a few things that earlier generations, with their more hierarchical management styles and relative geographical insularity, never really had to learn. One of those is collaborative decision-making that might involve team members scattered around the world, from Beijing to Barcelona to Boston, whom the nominal leader of a given project may never have met in person. “By 2019, every leader will have to be culturally dexterous on a global scale,” says Reid. “A big part of that is knowing how to motivate and reward people who are very different from yourself.”

They don’t teach that in B school — at least not yet. In fact, Rob Carter, chief information officer at FedEx, thinks the best training for anyone who wants to succeed in 10 years is the online game World of Warcraft. Carter says WoW, as its 10 million devotees worldwide call it, offers a peek into the workplace of the future. Each team faces a fast-paced, complicated series of obstacles called quests, and each player, via his online avatar, must contribute to resolving them or else lose his place on the team. The player who contributes most gets to lead the team — until someone else contributes more. The game, which many Gen Yers learned as teens, is intensely collaborative, constantly demanding and often surprising. “It takes exactly the same skill set people will need more of in the future to collaborate on work projects,” says Carter. “The kids are already doing it.”

Yes, We’ll Still Make Stuff

By DAVID VON DREHLE

The death of American manufacturing has been greatly exaggerated. According to U.N. statistics, the U.S. remains by far the world’s largest manufacturer, producing nearly twice as much value as No. 2 China. Since 1990, U.S. manufacturing output has grown by nearly $800 billion — an amount larger than the entire manufacturing economy of Germany, a global powerhouse.

But growth does not mean jobs. While sales soared (at least until the recession), manufacturing employment sank. Using constantly improving technology to make more-valuable goods, American workers doubled their productivity in less than a generation — which, paradoxically, rendered millions of them obsolete.

This new manufacturing workforce can be seen in the gleaming and antiseptic room in Southern California where Edwards Lifesciences produces artificial-heart valves. You could say the small group of workers at the Edwards plant, most of them Asian women, are seamstresses. Unlike the thousands of U.S. textile workers whose jobs have migrated to low-wage countries, however, these highly skilled women occupy a niche in which U.S. firms are dominant and growing. Each replacement valve requires eight to 12 hours of meticulous hand-sewing — some 1,800 stitches so tiny that the work is done under a microscope. Up to a year of training goes into preparing a new hire to join the operation.

Highly skilled workers creating high-value products in high-stakes industries — that’s the sweet spot for manufacturing workers in coming years. After an initial surge of enthusiasm for shipping jobs of all kinds to low-wage countries, many U.S. companies are making a distinction between exportable jobs and jobs that should stay home. Edwards, for example, has moved its rote assembly work — building electronic monitoring machines — to such lower-wage and -tax locales as Puerto Rico. But when quality is a matter of life or death and production processes involve trade secrets worth billions, the U.S. wins, says the company’s head of global operations, Corinne Lyle. “We like to keep close tabs on our processes.”

Recent corner-cutting scandals in China — lead-paint-tainted children’s toys, melamine-laced milk — have underlined the advantages of manufacturing at home. A botched toy is one thing; a botched batch of heparin or a faulty aircraft component is quite another. According to Clemson University’s Aleda Roth, who studies quality control in global supply chains, the successful companies of coming years will be the ones that make product safety — not just price — a “big factor in their decisions about where to locate jobs.”

Innovative companies will also stay home thanks to America’s superior network of universities and its relatively stringent intellectual-property laws. Consider, for instance, the secretive and successful South Carolina textilemaker Milliken & Co. While the rest of the region’s low-tech, backward-looking textile industry was fading away, Milliken pushed ahead, investing heavily in research and becoming a hive of new patents.

U.S. manufacturing will also be buoyed by a third source of power: the American consumer. Even in our current battered condition, the U.S. is the world’s most prosperous marketplace. As global economic activity rebounds, so will energy prices. The cost of shipping foreign-made goods to the U.S. market will begin to offset overseas wage advantages. We saw that last year when oil prices zoomed toward $200 per barrel.

Thus, even if fewer cars are built by America’s wounded automakers, there will still be plenty of car factories in the U.S. They will be owned by Japanese and Chinese and Korean and German and Italian firms, but they will employ American workers. It just makes sense to build the cars near the people you expect to buy them.

Raised on images of Carnegie and Ford, we rue the loss of once smoky, now silent megaplants but are blind to the small and midsize companies replacing them. Ultimately, what’s endangered is not U.S. manufacturing. It is our deeply ingrained cultural image of the factory and its workers.

The Last Days of Cubicle Life

By SETH GODIN

When Frank Lloyd Wright unveiled the Johnson Wax Building in 1939, it showcased a new way of looking at work. One room, covering half an acre (0.2 hectare), was filled with women, lined up in rows, typing. Work didn’t necessarily mean loud, dirty factories, but it still involved sitting in orderly rows, doing orderly work for a finicky boss.

In order to understand what your workplace is going to be like in five or 10 years, you need to think about what your work is going to be like. Here’s a clue: employers no longer need to pay you to drive to a building to sit and type. In fact, under pressure from an uncertain economy, bosses are discovering that there are a lot of reasons not to pay you to drive to a central location or even to pay you at all. And when work gets auctioned off to the lowest bidder, your job gets a lot more stressful. (See pictures of cubicle designs submitted to The Office.)

The job of the future will have very little to do with processing words or numbers (the Internet can do that now). Nor will we need many people to act as placeholders, errand runners or receptionists. Instead, there’s going to be a huge focus on finding the essential people and outsourcing the rest.

So, are you essential? Most of the best jobs will be for people who manage customers, who organize fans, who do digital community management. We’ll continue to need brilliant designers, energetic brainstormers and rigorous lab technicians. More and more, though, the need to actually show up at an office that consists of an anonymous hallway and a farm of cubicles or closed doors is just going to fade away. It’s too expensive, and it’s too slow. I’d rather send you a file at the end of my day (when you’re in a very different time zone) and have the information returned to my desktop when I wake up tomorrow. We may never meet, but we’re both doing essential work. (See pictures of office cubicles around the world.)

When you do come in to work, your boss will know. If anything can be measured, it will be measured. The boss will know when you log in, what you type, what you access. Not just the boss but also your team. Internet technology makes working as a team, synchronized to a shared goal, easier and more productive than ever. But as in a three-legged-race, you’ll instantly know when a teammate is struggling, because that will slow you down as well. Some people will embrace this new high-stress, high-speed, high-flexibility way of work. We’ll go from a few days alone at home, maintaining the status quo, to urgent team sessions, sometimes in person, often online. It will make some people yearn for jobs like those in the old days, when we fought traffic, sat in a cube, typed memos, took a long lunch and then sat in traffic again.

The only reason to go to work, I think, is to do work. It’s too expensive a trip if all you want to do is hang out. Work will mean managing a tribe, creating a movement and operating in teams to change the world. Anything less is going to be outsourced to someone a lot cheaper and a lot less privileged than you or me.

Godin is a popular blogger (sethgodin.typepad.com) and the author of 12 international best sellers. His most recent book is Tribes.

Source: TIME Magazine

Trackbacks/Pingbacks