Jim Collins got it wrong. Not totally wrong, but wrong enough that we need to be careful (as always) about who we listen to when designing companies for future success. Too often, leaders take a shortcut and blindly apply models they find somewhere else, without doing the work to adapt it to their culture and context.

Jim Collins is, of course, the international superstar guru author of “Built to Last” (buy at Kalahari.net or Amazon.co.uk), “Good to Great” (buy at Kalahari.net or Amazon.co.uk), “How the Mighty Fall” (buy at Kalahari.net or Amazon.co.uk), and “Great by Choice” (buy at Kalahari.net or Amazon.co.uk). His first two books are the two best selling business books of all time. His latest two seem bound to follow suit.

Collins’ focus as a management guru is simple and elegant: he is obsessed with what companies – and the leaders who lead them – do to be successful. His messages to business have also been consistent, and consistently simple, over two decades. The Economist, 26 Nov 2011 edition had an excellent piece on Collins’ contribution to management thinking.

I have to declare that I am not the wildest fan of Mr Collins. I have read too many reports from the research teams that have worked with/for him, and are very disgruntled at how he has used their work without giving them any credit. When I received my copy of “How the Mighty Fall” I was amazed to turn to the back cover of the book and see a single quotation, made by none other than… Jim Collins. I wonder if “hubris” and “arrogance” are possible ingredients in how the mighty fall? (Certainly “humility” was a key element of his “Level 5 Leadership” principle). I’ll say more on this at the end of this (long) post…

But, then again, maybe I’m just jealous. He is probably the most successful and influential management guru of our time.

That personal comment aside, though, the question nevertheless remains: Are the models Jim Collins presents worth following? This is especially important since two of his “Good to Great” companies have recently gone bankrupt (and one has destroyed billions of dollars of taxpayer money), and on average the whole lot have performed WORSE than the general stock exchange index over the past few years of recession. Are the principles in Collins’ books eternal? Or do they belong to an era that no longer exists? Or were the companies he selected just lucky? And, whatever the answer to these questions, one more is vital: can you achieve success by following his principles?

Jim Collins and his research staff are truly dedicated and talented professionals who have completed volumes of quality research on what it takes to build enduring and successful enterprises. That being said, the key to understanding, validating, and appropriately applying any form of research is to understand the context in which it was developed, as well as the business logic that was used to frame it. Let’s quickly review what he’s said.

A long line of books that went seeking the elusive X-factors

Nothing much is said these days about “Built to Last” – the principles in that book were soon replaced by the Good to Great set. But both books have the same problem. They choose old, established companies in old, established (mainly industrial era) industries. The reason for doing this is to avoid picking up young upstarts who might just be lucky (e.g. Amazon, Google or Virgin?). They looked for companies that had gone through multiple business models and multiple product streams, looking for the principles of what made them enduring and what made them better than their competitors. The measurement, however, was purely stock price – nothing else.

As with any studies of this kind, history can be cruel. Tom Peters collaborated with Robert Waterman to publish “In Search of Excellence” in 1982. They used the McKinsey “7s” model and also developed the following eight themes in the 43 of the Fortune 500 companies they surveyed:

- A bias for action, active decision making – ‘getting on with it’.

- Close to the customer – learning from the people served by the business.

- Autonomy and entrepreneurship – fostering innovation and nurturing ‘champions’.

- Productivity through people – treating rank and file employees as a source of quality.

- Hands-on, value-driven – management philosophy that guides everyday practice – management showing its commitment.

- Stick to the knitting – stay with the business that you know.

- Simple form, lean staff – some of the best companies have minimal HQ staff.

- Simultaneous loose-tight properties – autonomy in shop-floor activities plus centralised values.

Peters has since said he would the following to this list now in the 21st century:

- Capabilities concerning ideas

- Liberation

- Speed

As early as 1984, however, it became clear that not all the companies profiled were “excellent”. Business Week even ran an article titled: “Oops. Who’s excellent now?” (November 5, 1984). Companies like Atari, DEC, NCR and others soon were no longer. Some people even joked about a “curse” of being included in Peters and Waterman’s book.

Built to Last

It was 10 years later, in 1994, that Collins and Porras published “Built to Last” (it was unheralded to start, and built serious momentum towards the end of the 1990s). What made the research different to Peters and Waterman (who have since indicated that they imposed various presuppositions on their data) is that it compared and contrasted 18 visionary companies with a control set of rivals. For instance, Boeing was compared and contrasted with Douglas Aircraft, Marriott was compared and contrasted with Howard Johnson’s, and Merck was compared and contrasted with Pfizer. The findings are based on what the “visionary companies” did that was different from their close competitors who had also achieved a high level of success. But, from 1926 through 1990 the comparison companies outperformed the general stock market by 2 times whereas the visionary companies outperformed the market by 15 times.

In 2007, Fast Company did a review of the 18 companies profiled in Built to Last (read it here). They said:

Ten years on, almost half of the visionary companies on the list have slipped dramatically in performance and reputation, and their vision currently seems more blurred than clairvoyant. Consider the fates of Motorola, Ford, Sony, Walt Disney, Boeing, Nordstrom, and Merck. Each has struggled in recent years, and all have faced serious questions about their leadership and strategy. Odds are, none of them today would meet BTL’s criteria for visionary companies, which required that they be the premier player in their industry and be widely admired by people in the know….

…

But let’s give credit where credit is due. For all of the companies that have fallen on relatively tough times, most, if not all of Collins and Porras’s picks do actually seem, well, built to last. Today (in 2007), every one of the 18 companies cited is still in business, still a household name, still producing lightbulbs or computers or cigarettes or services or experiences.

…

Taken as a whole, the basketful of companies had a total shareholder return of 206% between August 1994 and August 2004, compared with 132% for the S&P over the same period. [The 18 comparison companies that still exist only returned 32% on average in the same period].

But, having said that, the BTL companies are not doing well now, during this last recession. And, even before it, they were struggling. Fast Company again:

Still, the fact remains that [at least 8] of BTL’s original 18 companies have stumbled — scarcely better than the results you’d get by flipping a coin. And that raises the infernal question that dogs the critical analysis of any business book: Have companies struggled because they ignored the principles in the book or because they followed them? “Gurus always grimace when one of the exemplary companies goes from good to great to goofus,” says Darrell Rigby, a partner at Bain & Co. and an expert on management trends. “Was that because management stopped applying the principles? Or because business conditions changed?”

It’s important to remember the context in which BTL was written – the heady early days of the tech revolution, when anything seemed possible:

BTL offered a message of hope and good feeling in an era when horizons seemed limitless: If you could unite your company around a system of core values that everyone actually believed in and goals that were wildly ambitious, you could have great success. “There are three critical success factors [with a business book]: One, tell people what they want to hear and give them hope. Two, make it a Rorschach test [inkblot test where its impossible to give a “wrong” answer], and three, keep it so simple that it really doesn’t examine the truth of the world in enough depth so people get a false sense of clarity.” BTL possesses all three.

Part of the problem

I think this last quote gets to the heart of it. In the heady days of the early to mid 1990s, you’d have had to be a fairly incompetent business to actually fail. Having big visions (Big Hairy Audacious Goals, as BTL put it) was clever. Add to that some generally good advice about decent management, and hit the start button. It all worked. So, well done to Collins for stating the obvious, backing it up with thud-value research to “prove” their points, and then promote the hell out of it. No harm done. Until the circumstances change, that is. Here’s Fast Company again:

In the end, though, there’s this one big rub about management books — even the best-selling ones and even the ones with plenty of data attached. The world they seek to describe is so complex, so tumultuous, often so random as to defy predictability and even rationality. “If Collins is to be faulted,” says James O’Toole, research professor at the Center for Effective Organizations at USC’s Marshall School of Business, “it is that he ignores Aristotle’s advice not to try to scientifically measure those things that don’t lend themselves to quantification.” And all the jumble and chaos mean, says Bain’s Rigby, that for every management theory, there is an equal and opposite theory that makes just as much sense. “Stick to your knitting, or don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” he says. “Better to be safe than sorry, but nothing ventured, nothing gained.” Perhaps BTL readers would do well to follow the title of chapter seven: Try a Lot of Stuff and Keep What Works. Now there’s some business advice worth taking.

But BTL was soon forgotten in the roaring success of the follow up book.

Good to Great

Published in 2001, “Good to Great” catapulted to the top of best seller lists, and became the theme of almost every corporate conference for the next few years. It’s now still a catch phrase for many companies and departments (at least, when your leader doesn’t know what else to say… “Let’s go from good to great, people!”). The book focuses on eleven companies that were just okay, and then transformed themselves into greatness — where greatness is defined as a sustained period over which the stock dramatically outperformed the market and its competitors.

The key principles are:

- Level 5 Leadership: Leaders who are humble, but driven to do what’s best for the company.

- First Who, Then Where: Get the right people on the bus, then figure out where to go. Finding the right people and trying them out in different positions.

- Confront the Brutal Facts: The Stockdale paradox – Confront the brutal truth of the situation, yet at the same time, never give up hope.

- Hedgehog Concept: Three overlapping circles: What makes you money? What could you be best in the world at? and What lights your fire?

- Culture of Discipline: Rinsing the cottage cheese.

- Technology Accelerators: Using technology to accelerate growth, within the three circles of the hedgehog concept.

- The Flywheel: The additive effect of many small initiatives; they act on each other like compound interest.

Now, I can bet that even those people are passionate about going from good to great could not, off the top of their heads, list those principles. Nor, I am guessing could many actually explain them. And even if they could spout what Collins said, I am prepared to stake my reputation on the fact that they could not adequately explain precisely what the principle would look like in their company. Take the most famous of them all: Level 5 Leadership. How do you identify one? How do you train someone to be one? What on earth does “Level 5” mean anyway?

When interviewed a few years back, Collins was asked whether Jack Welch was a Level 5 leader? He completely ducked the question, eventually answering, “Well, only Jack really knows whether he was or not”. What good is that to the CEO selection committee at your company?

Also little noticed by those who quote the book as scripture is that the chapters are in fact in a specific order. Although all the elements of “Good to Great” work together, there is a specific order about how the companies implemented the principles. As Collins repeatedly points out, none of the 11 companies had a single transformation moment. They developed into great companies slowly, over time. But, first they had the right leaders. Then, they got the right people. Then, they were realistic about where they were, and started to focus and become disciplined. They then applied technologies – or took advantage of fortuitous technological breakthroughs – and then it all started going right. (I’d add that most of them were probably lucky, too – but more of this in a moment). How many companies who have tried to go from “good to great” have followed this process, in order? Very few, I’d guess.

Analysing Good to Great

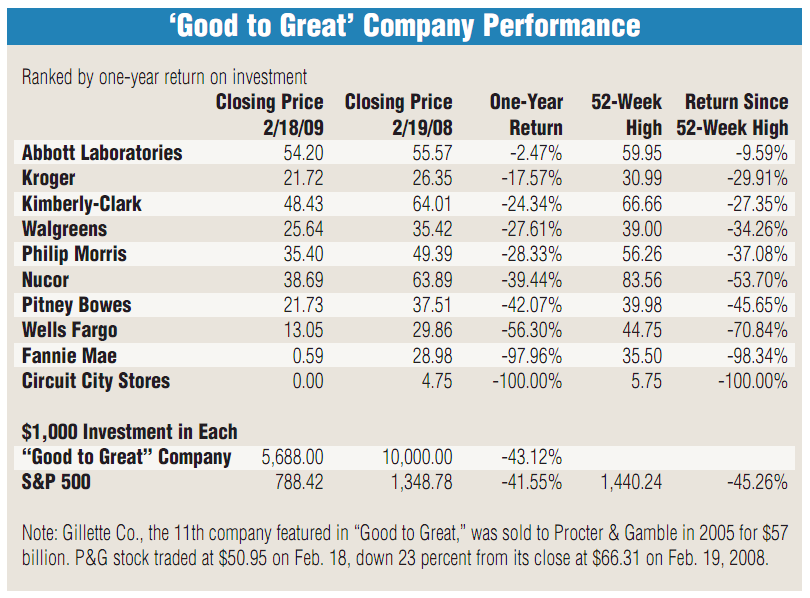

The person who has done the best analysis of the 11 GTG companies is Jeff Hankins, who’s February 2009 analysis showed that these companies have (collectively) underperformed the S&P 500 index on the NYSE over the period of the first two years of the recession. Read his analysis here. There is a PDF to download, or see this diagram produced by Hankins:

One of the 11, Gillette Co., isn’t in the picture because the firm was sold to Procter & Gamble in 2005 for $57 billion. P&G shareholders saw a 23% decline in value during the next few years. Of the remaining 10, two companies have gone from good to great to disaster: Circuit City Stores and Fannie Mae. Both are bankrupt – Fannie Mae only saved by government bail out because it was too big and important to be allowed to fail, but since discovered to have destroyed billions of dollars of tax payers money. Wells Fargo was down 56% (although, to be fair, it had performed better than Citigroup, Bank of America and many other competing financial institutions).

The others sit in the mid table, with Abbott and Kroger fairing the best (2.5% down and 18% down respectively). In 2008/9, Collins’ “great companies” declined by 43.12% compared with 41.55% for the S&P 500.

That’s not great, really, is it?

Wharton summed it up for me in this summary of Good to Great (which they were not that impressed with):

Collins asks an interesting question. Unhappily, the methodology he used to formulate an answer is questionable and the answer is almost disappointing in its simplicity: Great companies become great by staying focused: focused on their products, their customers and their businesses. They aspire to higher levels of excellence, are never content to become complacent and are passionate about their products. They have leadership that is not ego-driven, and have organizational cultures that embrace constant change. That’s the book.

I am not going to say much about his newest two books. The insights are a little too fresh to analyse just yet. But I think my case is made, and so we must progress to our most important question:

Should we read these books?

Yes. It’s simple: there is still value in reading the book. There are some good ideas – like the “stop doing” list. But BE CAREFUL! There is a danger to treat the principles as incontrovertible truth. And there is possible damage that will be done to apply the principles with no regard to the markedly changed business context we now face as we emerge from this worst-in-a-lifetime recession.

First of all, the good-to-great principles are true in the same way a horoscope is true. They are basically generic and thus we all apply them from our own viewpoint to make them true. The principles Collins proposes aren’t bad ones, but they are ambiguous and open to interpretation. This obviously decreases their usefulness – since you can’t really know whether you’re applying the principles as envisaged by the research into real good to great companies. For instance, Collins says GTG companies practice “First Who, Then What”. This basically means they hire good people. How does this help your recruiters? After reading the chapter, you really don’t have a better idea of how to do it, do you? And how many companies were deliberately hiring bad people in the first place? So, this is no help at all in taking you from good to great.

Level 5 leadership is equally vague. The only trait people seem to agree on is that level 5 leaders have humility. But beyond that, how is this principle helpful? And, assuming Collins is right, how many truly humble leaders do you really know?

Hankins, in his analysis, adds a further concern:

A Lack of Disconfirming Research

I’ve read all the notes in the book about how the research was done, and I think Collins and his team made a huge mistake. The good-to-great qualities, once determined, were never used to search for counterexamples. What I mean is that Collins and his team never said “are there any companies that have all of our good-to-great qualities that weren’t good-to-great?”.

Humans have a confirmation bias. We look for things that validate our preconceptions. But when you reach a conclusion you have to say “what would it take to prove this conclusion false?” And I understand why they didn’t. Because these principles are vague and it would be hard to debate whether or not an unsuccessful company was doing these good-to-great things. You could always say a company is in the process and will soon be great. Or you could say so and so isn’t a *real* level5 leader. I tried to find some examples, but I kept coming back to the same questions. How can you definitely say whether or not a company is following the good-to-great principles? You can’t.

Another author who has had serious issues with Collins (and other “gurus”) is Phil Rosenzweig. In his 2008 book, The Halo Effect (see a review and summary here, and buy it at Kalahari.net or Amazon.co.uk), Rosenzweig expresses concern about the research methodologies Collins used:

What They Don’t Know

Collins also doesn’t know what he doesn’t know. In other words, maybe there were causes that he and his research team were not aware of. Perhaps executives at the good-to-great companies better understood the economics of their industry. Or maybe they were more financially saavy and understood how money flowed through the company and where their profit really came from. It is common for companies not to really understand these things fully. But Collins would have no way of uncovering that, and even if he did, who would write a book that encourages would-be business leaders to study up on the economics of their industry and better analyze cash flow statements? It wouldn’t sell very well because that stuff is boring and hard.

Lucky

I am even more concerned that these companies, their leaders – and possibly Collins himself – are simply lucky. The right products, together with the right business culture, in the right markets, bumped up by the right technology, and just the right time – and you get a success. Given the number of companies out there, statistically this is bound to happen. But, when the business context changes, you’ll find out whether it was design or luck.

At this stage, one could argue that both BTL and GTG companies could be considered lucky, rather than strategic. Equally the fallen “Mighty” companies might just have been unlucky.

I am not saying that they’re leaving things to chance. Nor am I saying these companies don’t have good strategies or good leaders. But I just am worried that the “principles” Collins thinks he sees are not the only – or even the most important – factors in their past success. I am even more concerned that the clients I work with don’t fall into the trap of trying to apply these principles in an environment – internal and external – that does not require them.

In a blog post, “Rethinking Good To Great“, Mike Hyatt said this in September 2008:

The problem with “Good To Great” is that the reader is left with the false impression that the principles contained in the book can be universally transferred to their individual situation without regard for context. The reader is led to believe that if they apply the principles contained in the book to their business that the results will mirror those of the companies examined in the book, and that their business will in turn make the leap from good to great and enjoy sustaining good fortune. This is simply not true. You see all research, even good research, must be evaluated contextually. There are very few universal truths in business that can be applied in a vacuum.

If you’re the CEO of a well branded, well capitalised large multinational with a long history, then the context of GTG companies might match yours. If you’re operating in a fast growing, globalised world with no credit constraints, irrationally exuberant customers and legislators, a war for talent, and are based in the USA, then maybe the operating environment of the GTG companies matches yours. If you’re not really impacted by changing technologies, decreasing resources in a warming world, or shifts in demographics, societal values and global institutions, then you might get value in learning lessons from the GTG companies. Otherwise, you’ll need to make adjustments for your own environment and operating context. Hopefully, you get my point!

And I have one further concern. What is greatness anyway? Collins uses stock price over an extended time period as his sole criterion. Tom Peters disagrees with this as the sole measurement:

Companies that Jim calls great have performed well. I wouldn’t deny that for a minute but they haven’t led anybody anywhere. I don’t give a damn whether Microsoft is around 50 years from now. Microsoft set the agenda in the world’s most important industry at a critical period of time, and that to me is leadership, not the fact that you are able to stay alive until your beard is 200 feet long.

So, what do we do about all this?

If you’ve made it to this point in this extended blog post, you might now ask, “so what?” What point am I trying to make.

For me, The Economist, summed it up best in their 26 Nov 2011 edition, when they reviewed Collins’ career as a management guru:

This is not to say that Mr Collins’s insights are worthless; merely that they are less robust than he suggests. Most business books would profit from a bit more rigour. Mr Collins’s might profit from a bit more willingness to admit that, like all management gurus, he is dealing in clever hunches rather than built-to-last scientific discoveries.

I suppose, to be honest, it’s a simple point that could have been made right at the start, and saved you a lot of minutes of reading. The point is this: there is nothing easy about leading a company. There are no simple, “one size fits all solutions”. Your task as a leader is first to understand your business context. Then, to understand your business culture. Context and culture are two things I find leaders are not very good at thinking about or articulating. But they are the basis of building great companies. You cannot import these things – you need to define and describe them. They exist already, and they can be changed.

This, for me, is the true task of leadership, and the best starting point for greatness.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks