Free agency is now 21 years old! This might not sound important, but spotting trends and learning from history is absolutely critical for future success.

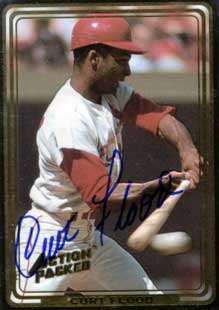

In 1975, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally won a court case against the reserve clause that had dominated baseball employment contracts for half a century. Basically, the clause meant the players were owned by their team and could not leave a team and play for someone else, unless they were traded or sold. The reserve clause had first been tested on January 16, 1970 by Curt Flood, when he filed a lawsuit claiming that the reserve clause violated the antitrust act and should be eliminated. Flood was one of the most talented and gifted baseball players of the 1960s, and retired soon after losing his court case against the Commissioner of baseball.

In 1975, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally won a court case against the reserve clause that had dominated baseball employment contracts for half a century. Basically, the clause meant the players were owned by their team and could not leave a team and play for someone else, unless they were traded or sold. The reserve clause had first been tested on January 16, 1970 by Curt Flood, when he filed a lawsuit claiming that the reserve clause violated the antitrust act and should be eliminated. Flood was one of the most talented and gifted baseball players of the 1960s, and retired soon after losing his court case against the Commissioner of baseball.

In 1976, 21 years ago, free agency was born. Players were free to move when and where they want to, as long as the market wanted them. They could charge whatever they wanted, as long as they could find someone to pay them. Their value was directly related to their talent. Other sports quickly followed suit, and by the end of the century most sports around the world were fully professional and in search of the top talent in their code.

Cary Grant had had done something similar in the entertainment business years before, when he bucked the studio system.

What started in the entertainment industry, spread to the professional sports environment, finally hit the corporate world in the 1990s. Fuelled by the Internet boom and the massive layoffs of the 1980s, the concept of free agency slipped slowly and insidiously into the consciousness of young, talented employees. Work is now for many people no longer a home away from home – it is a place to go to simply make money. Loyalty doesn’t exist. Talented people are aware of the value to the company and inherently understand that they are free agents. They should be paid for their contributions, recognised for their abilities, treated differently and and their performance and return on investment measured.

One of the big mistakes that baseball owners made in the 21 years of free agency is to pay all of their players – stars and utility players – inordinate salaries. Unions have dominated baseball, and forced up minimum wages to ridiculous levels. Baseball has failed to understand the difference between top stars – their talent – and average players. Average players can easily be replaced. But when they are paid as much as talented players, the return on talent drops dramatically. The same is true in the corporate world, and with a two decade lag in free agent thinking, maybe its time for the corporate world to consider space some of the lessons that could be learned from other industries that have more experience of this new type of employee.